Knitwear: Garments for All Seasons

By Sean Longden

First mankind tamed dogs. And once he had tamed dogs, he gathered flocks of sheep and goats, controlling them with his dogs. And, for as long as man has kept sheep and goats, mankind has been wearing woollen garments. In wool, ancient tribes and nomad people discovered a fabric whose durability and versatility kept them cool in the day and warm at night. In the rain, it absorbed moisture without the wearer feeling wet. In the wind it protected them yet was light and flexible enough to allow them to keep moving. And whether you call it a jumper, a jersey or a sweater, the knitted outer garment remains as relevant today as it ever has been.

Whether knitted or woven, it was wool that allowed men to keep warm and to explore the far reaches of the planet. Whether heading across polar ice, sailing uncharted waters, or climbing mountains simply because they are there, it was woollen garments that kept explorers insulated. Most importantly, it was the freedom given to them by knitted garments, which stretched and twisted without hindering the movement of their limbs, which was were essential to their efforts. And, even in this age of technology and manmade fibres, knitted woollen clothing still accompanies astronauts into space. It is truly a garment for all places and all seasons. See below our newly launched Quarter Zip Jumper.

For thousands of years wool has been at the centre of the clothing trade. By 10,000 BC there were wool weavers in Mesopotamia and among the Northern European tribes. Their tools were basic but it was the beginning of an important step in mankind’s development. With the rise of the Roman Empire, flocks of sheep could be easily moved around the continent to spread the trade. And to improve the quality of their wool, the Romans selectively bred their animals to produce finer and stronger wool.

Roman Britain became an important base for the Empire’s wool production, with the Romans valuing the skill of the local weavers. The richest cities of medieval Britain were those in England involved in the wool trade, with skilled Flemish weavers moving to eastern England to exploit their talents. By the late seventeenth century, two-thirds of England's foreign commerce was based on the export of woollen textile. Shepherding, shearing, teasing, carding, spinning, weaving and knitting were the skills at the heart of this trade.

Whether the finest woollen stockings for noblemen or the jumpers worn by sea fishermen, for hundreds of years it was the hand knitters who sat and laboured for hour upon hour to produce clothing. Then in the late 16th Century came the industry’s greatest advance: William Lee’s invention of the knitting machine. The first machine was basic, relying on the operator to lay the yarn onto the frame by hand. In these early days the machinery was primarily used in the manufacture of the woollen stockings worn by men and women alike. However, records show that Lee’s machine was also used to produce other garments such as knitted waistcoats. By the end of the 18th Century the machinery had advanced to allow the yarn to be threaded into the machine with foot operated treadles and for ribbed stockings to be produced.

With the industrial revolution change came rapidly with card systems, already in use among silk weavers, allowing for patterned knits to be created. As hand-knitters were put out of work they revolted against the new machinery, rioting and smashing the technology that was putting them out of work. Despite their best efforts they couldn’t prevent progress and the first half of the 19th Century saw rapid progress courtesy of two Frenchmen, Pierre Jeandeau and Marc Brunel, who designed a machine with a circular, rather than flat arrangement. Next came Matthew Leo Townsend who, in 1849, patented an upright circular machine complete with latch needles. Townsend was from the English city of Leicester, in the East Midlands, which was to become one the UK’s major knitting centres, home to company’s such as Wolsey which started out as a hand knitting company and went on to provide the woollen underwear used by both Amundsen’s and Scott’s teams as they raced to the South Pole. Others areas of the East Midlands also became important knitting centres, such as Nottingham and Matlock in Derbyshire, where the John Smedley company still runs the world’s longest continuously operating factory, which has been making knitwear since 1784.

Matthew Townsend later emigrated from Leicester to America, taking his designs with him. With the coming of American Civil War his machines were prized for their ability to create high quality socks for the Union army. Machinery swiftly improved to allow shaping and the adding of ribbed cuffs, thus improving the comfort and fit of his socks. The American engineer Henry Griswold patented a number of improvements to knitting machines, many of which are believed to still be in commercial use. Realising the potential of his new machines, he soon patented his designs in Europe: The age of mass produced knitwear had truly arrived.

At first the knitting machines were dedicated to the production of socks and stockings. For fancy designs it was the hand knitters who still dominated the trade. Coloured patterns and textured designs were the preserve of individual groups of knitters. The Fair Isle patterns - that include anchors, ram's horns, hearts, ferns and flowers - reflected the nature of island life and the colours were restricted to dyes produced by the island’s native plants. On the Aran Islands the traditional patterns were designed to represent individual clans, allowing the bodies of fishermen lost at sea to be identified if they washed ashore. They also used heavily oiled wool which helped to keep the fishermen dry whilst at sea. Similarly distinctive patterns were used in the Channel islands where the island of Jersey gave its name to the generic term for a knitted garment and Guernsey produced the ‘Gansey’, a cable knit fishing jumper that is traditionally produced in blue wool. One distinctive feature of the Gansey design was that both front and back are knitted identically, allowing the jumper to be worn either way round, thus helping to minimise wear at stress points such as the elbows. Elsewhere, Norway developed the selburose pattern of snowflake like stars which is widely imitated worldwide and remains instantly recognisable as Nordic knitwear. The popularity of heavy knitwear among seafarers has survived the years, with submariner sweaters going from comfortable garments favoured by the officers and men of the Royal Navy to being a fashionable 21st Century favourite.

However, with the arrival of mass production courtesy of knitting machines, the industry was able to rival the intricacies of the traditional hand knitter’s art. Industrialisation meant that a pattern, that had once been the preserve of a handful of women in remote island cottages, could now be transferred to a card-system and be copied by factories around the world. What might take the hand knitter days of intensive labour could now be produced in minutes.

Extremely heavy knits were developed in the USA and Canada where thick woollen cardigans allowed workmen to move freely even in the cold of winter. They were worn long on the body, preventing them from riding up and exposing the body to the cold, thus earning themselves the name ‘Sweater Coats’. Some of these heavy knits mimicked the stylings of the popular fashion for Norfolk jackets, complete with belts, straps and multiple pockets. These became popular for sports, in particular among golfers many of whom had previously worn Norfolk jackets but preferred the freedom of movement allowed by their knitted substitute. Shawl collars were popular on these styles as they allowed the collar to be turned up to increase protection against the elements. These garments could also be worn around the home, giving the wearer both warmth and comfort as he replaced his jacket after a hard day’s work. They also retained a degree of formality, allowing a man to feel both adequately dressed and suitably relaxed.

The late 19th and early 20th Century saw the development of another enduring style of cardigan, the Cowichan. Also made long and featuring a shawl collar, the Cowichan was originally produced by members the Cowichan people, a First Nations tribe from Vancouver Island. The style developed to incorporate sporting designs featuring popular Canadian winter sports and can now be found with curling, skiing, ice skating and ice hockey designs.

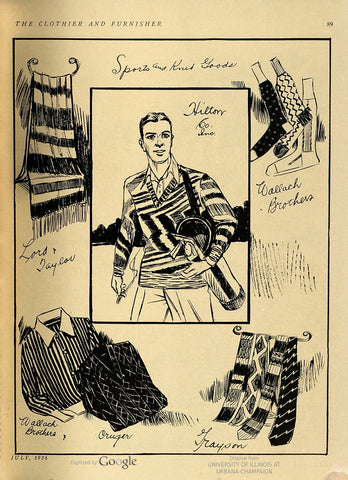

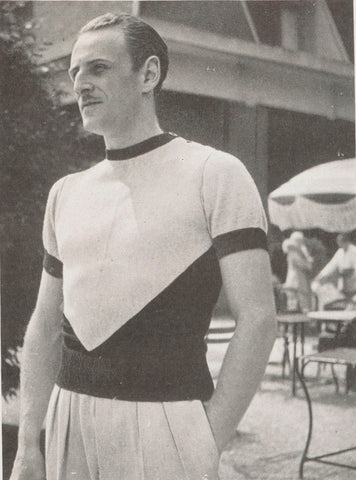

In the early 20th Century increased leisure time meant that knitwear became increasingly popular for cyclists who enjoyed the freedom of movement that knits allowed. And, as professional and amateur team sports became increasingly popular, knitted sportswear was everywhere: cricket and tennis jumpers sported club colours and ice hockey teams emblazoned their logos across the front.

If such casual styles were increasingly popular in the early years of the 20th Century, it was in the aftermath of the First World War that knitwear really came into its own. During the 1920s, knitwear moved away from being simply practical garments designed to keep people warm. Instead it was launched into the world of fashion and caught the attention of a world bored by the drab colours of wartime. The increased use of worsted yarns meant that knitted garments were no longer rough and best suited to winter; instead they could be made with a smooth texture meaning they could be worn in all seasons and introduced a new elegance to knitted garments.

Legend has it that the Prince of Wales’s choice of a Fair Isle jumper for golfing helped to spread the fashion for Fair Isle patterns to a wide audience. However, in another version of the story, the spread and popularity of the style in the aftermath of the First World War was actually was a result of sailors from the Royal Navy who purchased knits whilst stationed in the Scottish islands.

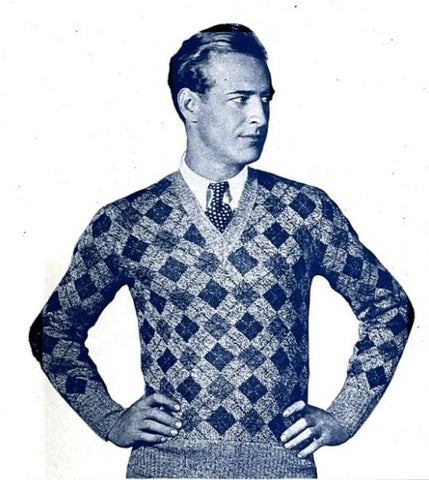

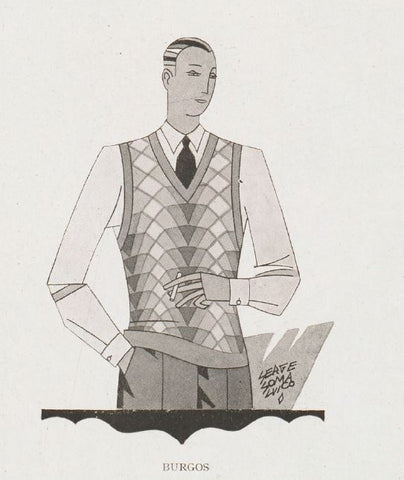

The future King was also thought responsible for the spread of popularity of the distinctive Argyle diamond pattern that was derived from the traditional tartan of Clan Campbell. To meet such fashion trends it was only the mass output of knitting machines that could meet the surge in demand. Companies such as Wolsey cashed in on this fashion and the boom for leisure, mass producing patterned golfing jumpers with matching socks, along with cricket and tennis jumpers. It wasn’t long before companies worldwide were copying and reinterpreting the designs for the mass market.

Suddenly knitwear was everywhere: In a look first attributed to the undergraduates of Oxford University, fashionable young men cast off their collared shirts and ties in favour of roll neck jumpers in elegantly fine cashmere in a variety of eye-catching colours that appalled traditionalists.

In the mid-1920s, bold art deco patterns could be woven into jumpers for those wanting to be on the cutting edge of fashion.

These new knitwear patterns were daring and radical, perfect for the ‘jazz age’ in which convention was being cast aside.

It was a look that was soon exaggerated and lampooned for comic effect on stage and in cinema:

With more people travelling for leisure, knitwear was ideally suited for holiday-wear. The French menswear companies set the trend with exciting patterned knits and luxurious resort wear knitted in silks and cottons. Brands such as Chanel, Sulka, Seelio and Knize offered a dazzling array of lightweight knits that saw the resorts of the French Riviera as a playground for men to parade their outfits as proudly as any of the women.

The same people who paraded the most fashionable lightweight knits on the Riviera in the summer also showed off their heavy knits on Europe’s ski slopes during the winter. With skiing enjoying a boom during the 1920s and 1930s, new styles of knitwear were being experimented with, see below our newly released Quarter Zip Jumper- the perfect Alpine sweater. Short knitted jackets, with pockets, lapels and collars, became popular. Patterned knits, in heavy wool, were popular along brightly coloured outside that were both fashionable and functional.

Of course, heavy knits were not just favoured by those fortunate enough to be wealthy enough to afford skiing holidays. At the other end of the social spectrum, heavy knits became popular as day wear, worn under a sports jacket as a handy way of keeping out the cold.

Factories, cottage industries and home knitters all turned out patterned cardigans and slipovers that were more comfortable than the constrictions of traditional waistcoats, or offered knitted waistcoats complete with four pockets and pointed fronts to recreate the stylings of a suit waistcoat in the comfort of a knit. Contrast cuffs and trim added a blast of colour to the garments. Sleeveless sweaters, some even with roll necks, became a firm favourite for those who needed their arms to remain free and their bodies to keep warm. Car drivers, weekend sailors and motorcyclists all understood the need for wool. To handle the desires of men to wear colourful and interesting patterned knitwear, there was a large industry which produced home knitting patterns, allowing those with limited resources to keep up with fashion.

Just as the tracksuits of the 21st Century are commonly worn as casual day wear, in the 1920s and 1930s cream cricket and tennis jumpers were the mark of the casual young man, regardless of whether he actually engaged in those sports. Indeed, brands like Champion in the USA, which started out as Champion Knitting Mills, produced high quality knitted jerseys that were favoured by sports teams. It was their efforts to refine knitted sportswear that helped develop reverse weave fabrics leading to the creation of lighter weight sports clothing, and eventually to the invention of the hooded sweatshirt. In addition, early 20th Century knitwear included garments in woollen curl-cloth, a textile that was warm and light and would eventually be reproduced in manmade fibres as the ubiquitous ‘fleece’ that is so popular in modern leisurewear.

As technology advanced, machines could easily knit designs in garments, allowing sports teams to show off their colours or for dark garments to be livened up with contrast cuffs, collars and waistbands. By the mid-20th Century this allowed for a variety of vivid designs that were perfectly in age with the new casual styles that emerged, especially in the aftermath of World War 2.

The cycle of fashion may have seen knitwear be replaced by lighter weight garments as the choice for sportswear, but knitwear retains its appeal for both a mass market which understands and appreciates wool’s versatility and the more discerning buyers who enjoy the craft and heritage of long established mills and independent knitters. The continued selective breeding of sheep and goats, a practice originally used to create thick and hardwearing wools, means that lighter and finer wools continue to be created for the luxury market. The refinements in manmade fibres – which were first used in knitwear in the early years of the 20th Century - means that pure wool can be blended with fabrics that help wool to retain its shape and prevent garments from losing their shape after multiple washes. Where once garments were pulled on over the head, technology has seen first buttons and now zips allow for a choice of fastenings.

And now, in the early years of the 21st Century, knitwear can be found in every style for every market: Crew necks, polo necks, shawl collars, roll necks, v necks, round necks … sleeved or sleeveless … heavy or smooth … every choice can be found: Cricketers and submariners still wear their traditionally styled garments, which look as iconic now as they did 100 years ago; Men still wear luxurious turtleneck jumpers under a jacket, a look that first emerged in the 1920s among British students; Fisherman’s jumpers are now more likely to be seen worn by a suburban housewife as by a man sailing the seas in search of cod; And 21st Century rockers can recreate the 1950s look with roll neck cream coloured jumpers under their leather jackets.

Wool may have come a long way since the days of mankind’s first nomadic sheep herders, but our appreciation of knitted wool shows no sign of abating.